My previous post explained how full strategic change may become attractive – even essential – when technology or other factors threaten to make our current business model obsolete.

It also stressed the need to control decline of the old business model, while in parallel building up the new. And this is tricky because old and new models will share many of the same resources – the same sales teams or supply chain for example.

Case: From IT outsourcing to business-process outsourcing

A historic case may bring the issues to life … Long ago, many companies realised that their core capabilities were about developing and offering their products and winning customers and sales – not managing their IT facilities! So they ‘outsourced’ that function to specialist IT firms, like Cisco and Infosys.

Initially, that just meant handing over their hardware and applications to those providers with a sigh of relief. But those providers were then left with a growing mess of obsolete and disparate hardware and software. So the IT-outsource (ITO) providers standardised the hardware and software applications they would support for their clients.

But the providers then realised they could go further and relieve clients of still more of their non-core activities if they offered entire business processes. Clients would never see the IT assets at all. An insurance company, say, would no longer have IT kit and software to handle policy-holders’ claims – the outsource provider would do all that. So business-process out-sourcing (BPO) was born.

BUT … the providers had many long-term ITO contracts with existing clients, often for 5-10 years. Also, at least in the early years, outsourcing their business processes looked risky to many clients.

So the outsource providers had to migrate their client base over many years. First, a client might move to some BPO contracts, while old ITO contracts ran their course. Eventually, all ITO contracts would be replaced with BPO contracts.

Migrate the customers

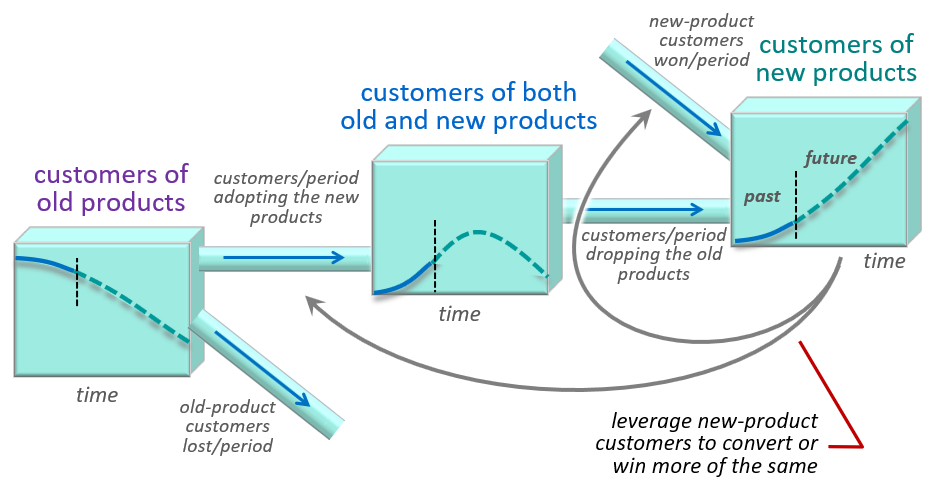

Let’s generalise this. When changing what we want customers to buy, we need to move them [1] from taking our old-type products to taking both old and new, and then [2] to taking only new-type products. (‘Products’ might be services, of course, or new ways of doing business with us).

Figure 1: Migrating customers from old-type products to new-type

HOW to encourage/manage customer migration?

I already shared how to get target groups to adopt a new behaviour with the “choice pipeline” – get them aware of the new option, then understand it, then trial it, then commit to it. And that’s what we have to do ‘inside’ both the first adoption of new-type products at left of this figure, and the winning of new customers at top-right.

Other implications of this transition model:

- we want customers to start adopting new products before choosing to leave us! (at bottom left)

- we would hope to capture entirely new customers to the new-type products (at top-right)

- growing customer numbers for new-type products can be leveraged to push others to migrate, through word-of-mouth or reference-site mechanisms – the feedback connections at lower right.

(I hope it’s clear that all of this is done with real-world, time-based numbers, not only on all of the items in this figure, but on all of the factors driving those items)

Where’s the cash!?

Let’s not forget that we wanted to do all this because the old-model’s cash flows would eventually die, and the new model’s cash flows needed to grow to replace, and hopefully overtake, those we would otherwise lose.

But it’s easy, now, to simply attach the cash flows to figure 1 (the revenues and margins from each customer group, minus the operating costs of realising and supporting those customers and revenues – it’s in this post and this one).

The big dilemma now is how fast to make this happen? Do we try to put off the day when we have to migrate from the old model to the new, to protect those old cash flows for as long as possible, or do we deliberately kill the old model by pushing customers over to the new model before they might have chosen to do so? (This is a strategic version of the challenge faced by companies offering successive generations of ever-improving products, so clearly set out in Prof Clayton Christensen’s great book ‘The Innovator’s Dilemma’)

More to come [C] ..

This post is already quite big, so I’ll leave it to next time, to explain the implications of such strategic change for staffing and product/service development. That will basically wrap up the topic.

The post Planning and managing full strategic change [B] appeared first on Kim Warren on Strategy.